Here are the names of some Symbolist authors I've been reading over the past couple of weeks:

Charles Baudelaire,

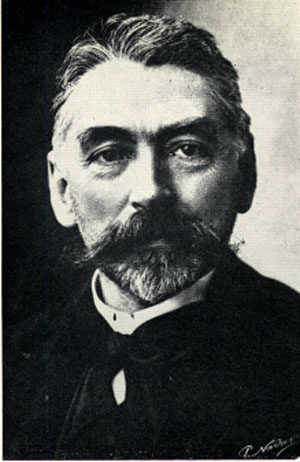

Stephane Mallarmé,

Jules Laforgue,

Paul Verlaine,

Arthur Rimbaud,

Auguste Villiers de l'Isle-Adam (on whom more later — this guy is

insane). What do these writers have in common? Nothing really very definitive, I would say, other than their historical placement in late 19th century France, and certainly nothing that can be meaningfully summed up by the term "Symbolism." (Arthur Symons writes, unhelpfully, that “[w]ithout symbolism there can be no literature; indeed, not even language” (3); so, these Symbolists, they tend to use words, then?) A better term might be "Vague-ism" (

la Vieille Vague?) since they all seem to make a point of avoiding the traditional precision of the French language in an effort to capture impressions, sensations, spiritual essences. Certainly there are some family resemblances beyond their vague interest in vagueness: viz., an orientation toward classicism and antiquarianism in general (Baudelaire, Mallarmé, Villiers); an abiding obsession with sin and apostasy left over from an (often lapsed) Catholicism (Baudelaire, Rimbaud, Villiers, Verlaine); a somewhat colloquial bent (Laforgue, Rimbaud, Verlaine); a tendency to compose lyric cycles (Baudelaire, Verlaine, Rimbaud); an interest in the English language, if not England itself (Verlaine, Mallarmé, Laforgue); a persistent attention to Paris and the habits of the bourgeoisie (Baudelaire, Laforgue); and,

bien sur, a concern with modernity and the "new" (Baudelaire, Rimbaud, Laforgue).

The term "Symbolism" is probably most apt for Mallarmé, who specializes in multiply overdetermined, head-spinningly allegorical literary symphonies like

L'Àpres-midi d'une jeune faune. Unsurprisingly he's the one Derrida likes best; see his essay "Mallarmé" in

Acts of Literature, where he appreciates SM's syntactical ambiguities and "chains" of signification which are "as if without support, always suspended." I probably like him least, if only because he's the most untranslatable into English and because the criticism about him is the most fatuous (although do I note that his endlessly extended streams of syntax probably had some kind of substantive influence on Proust).

It's been interesting to juxtapose my exploration of this colorful cast of characters with my continued reading of Marx, and specifically “The Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Napoleon,” his exhaustive account of the deterioration of the French Second Republic (1848-1852) into the neo-imperial era of Napoleon III. The impression I get from this essay is that Paris, beginning in the latter half of the nineteenth century, is largely struggling to

deradicalize itself, even within the republic's own ranks. Marx brilliantly shows how every political move made by the bourgeois-controlled social republic was made in the name of restoring order, regularizing trade, and preventing another bloody revolution. Essentially it was this republican timidity and caution, Marx argues, that allowed Louis Bonaparte, Napoleon's nephew and (in Marx's view) a thoroughly uninspiring figure, to gain the support of the French peasantry and accomplish his

coup d'état, thus establishing the Second Empire, the milieu of Baudelaire's

Les fleurs du mal.

And it does seem to me that Baudelaire, and the Symbolists later on, for all their ostensible hatred of the bourgeoisie and deliberate provocation and strangeness, are essentially engaged in the same process of deradicalization that Marx describes so well in "The Eighteenth Brumaire." Baudelaire's, and later Laforgue's, cynical portraits of Parisian society in fact tend toward a reification of the social order: as if it were an easier way forward for artists to make themselves marginal in a capitalist society than risk being made irrelevant in a socialist one; or, worse, having their ultimate relevance endlessly deferred in the name of a society that never arrives.

I don’t know if you guys have read Walter Benjamin’s essay “The Paris of the Second Empire in Baudelaire,” but it very compellingly represents CB as a sort of ghostly figure walking through the limbo of early late capitalism, inhabiting an economically prosperous but spiritually barren period in which Republican ideals were being sacrificed to “order.” In such times, a lyric poet like Baudelaire is more or less forced to throw in his lot with the bourgeois, who are the ones trying to maintain a society in which poetry can have any kind of place; but this necessitates accepting a very marginal position within that order, and one which is gradually pushed further and further to the margins, in much the same way as the interests of the proletariat are betrayed over time by the compromises of bourgeois republicans (in Marx/Engels' view of things, at least). Hence Benjamin's great claim for Baudelaire, that he “was a secret agent — an agent of the secret discontent of his class with its own rule” (261): i.e., a poet who was fated not to envision a new society, but instead to reflect on and criticize the only order that would allow him to exist at all.

The big question here, I suppose, is why the Symbolists weren’t more politically engaged (in their work, I mean; Rimbaud, Villiers, and I think Verlaine did briefly fight alongside the Paris communards), given that they were so deeply dissatisfied with bourgeois society in an era in which there were more than a few opportunities to try and do something about it. The reason I’m inclined to give is that writers, when they’re being “political,” aren’t just reacting to political realities: they’re reacting to the history of literature, which is no less real to them for being essentially an illusion. In other words, the Symbolist ennui is not simply a reaction to bourgeois progress, it's also a reaction to Romanticism, a mode which they would have associated with a certain revolutionary fervor. It does seem like Romanticism, in France, was much more of a political project than it was in England (or in Germany? don't know much about Germany). There, the poetic "revolution" of Romanticism corresponds, roughly, to a political revolution: and this revolution is then exhaustingly prolonged, and partially betrayed, over the course of more than a century. By the time of Baudelaire, let alone that of Rimbaud and Verlaine, there is an exhaustion with the very concepts underlying the revolutionary and the “modern.” At the same time, there’s a sense that the modern has not yet really arrived: that the world heralded in the literary works of Hugo and c. is not in fact the one in which they themselves are living. This discrepancy manifests as an almost pathological hatred of the complacent bourgeoisie (as in Flaubert) but also as a hostility to idealism and to the narratives of progress that were so crucial to revolutionary politics (and certainly to Marxism).

To put it another way: French literature never had the time to really

enjoy its Romanticism. It was too busy trying to maintain the state of human affairs that Romanticism had encouraged them toward, that Rousseau and Lamartine and Victor Hugo taught them to desire. England, on the other hand, had a little

too much time to play around with the consequences of Romanticism, ironically as a result of refraining from demanding its ideals as a life-condition; and the result of this is the sort of hypertrophy of imaginative sensibility, unrealized but endlessly elaborated. Indeed, there's a surprising formality of French poetry even in the Symbolist period: I think part of what's interesting about the Symbolist poets, perhaps Verlaine and Rimbaud in particular, is that their elaborate self-involvement is forced into forms that don’t really lend themselves to it. They tend to favor sonnets and other strict metrical forms, and hardly ever abandon rhyme. As far as I know it doesn’t seem as though any French poet before 1900 even goes as far as blank verse — if they want to do away with rhyme, then they just write in prose. So there’s nothing comparable to Wordsworth’s

Prelude in French, for instance, or (to choose a more contemporaneous example) Swinburne’s endless “narrative” poems.

This is the pragmatic, or formalist, or literary-historical, way of explaining Symbolism's apoliticality. But to try again, in a more theoretical register: maybe an aesthetic like Symbolism, by its very nature, can't be (politically) revolutionary: perhaps it needs an established order, to ground its flights into the empyrean and provide it with iconography to distort and deform: unlike Romanticism, it’s essentially not progressive but ruminative and speculative. Baudelaire writes in "Le Cygne":

Paris change, mais rien dans ma mélancolie n’a bougé! (Paris changes, but it’s nothing compared to how my melancholy soul moves.) You can’t say something like that with conviction when you’re trying to

make Paris change: your concern is with how fundamentally separate your soul is from the order which, nevertheless, goes on without and around you. (Ironically, though, it is nineteenth-century France’s unionizing tendency — its habit of grouping its citizens into movements, of issuing manifestoes — that renders even such a- or anti-political aesthetics as Symbolism and

l’art pour l’art visible, and therefore possible; as Arthur Symons puts it in his introduction to

The Symbolist Movement in Literature: “France is the country of movements, and it is naturally in France that I have studied the development of a principle which is spreading throughout other countries, perhaps not less effectually, if with less definite outlines.” And I would argue that the artists of England and America had to struggle to make their homelands into "countries of movements" to be able to have Modernism in the first place.)

Hope some of this makes some kind of sense; I feel like I'm starting to get somewhat "vague-ist" myself. What I want to register primarily, I guess, is the irony of the first stirrings of the twentieth century’s aesthetic avant-garde turning out to be so deeply intertwined with an antipathy not just for the modern (

that we expect) but also for the revolutionary, and even the socially progressive.

Georg Simmel feels your pain:

Georg Simmel feels your pain: