Yep, it was literary critics killed Modernism, not poets (though many of them poet-critics: not exactly sure what to make of that). And it was accomplished not through any sort of polemical attack, but through a simultaneous collective lowering of expectations, and a willingness to rest on laurels. We know everything we need to know, the argument ran, to write great poetry now: and if you don't know, you haven't been paying attention. In that case, God help you.

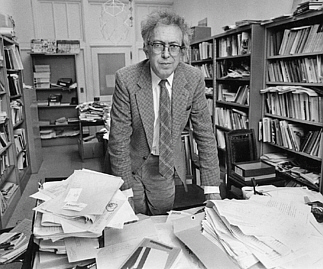

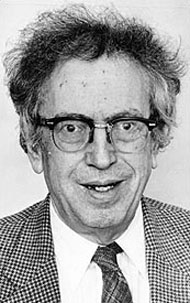

Exhibit A: R.P. Blackmur's "Lord Tennyson's Scissors: 1912-1950," an overview of the Modernist period published in 1951 as the epilogue to his collection

Language as Gesture. "Forty years of poetry took their rise in Eliot, Yeats, and Pound," Blackmur says, condensing a half century's worth of complex aesthetic and political wrangling into three Big Names to set alongside Shakespeare-Marlowe-Jonson, Wordsworth-Coleridge-Southey and Shelley-Keats-Blake. I'm just going to quote some (OK, a lot of) stuff from this essay, because some of it is helpful, a lot of it is funny (and unfair), and all of it gives a good index of how even the most pro-Modernist critics wanted to wrap things up and move on to the next thing by the beginning of the 50s:

On Yeats: "neither his vices nor his poetry ever quitted him" (424)

On 1922: "1922 seems the great year of our time — especially if you let the months run a little both ways — for it holds a good many of Yeats' Tower poems, Pound's first eight Cantos, and Eliot's

The Waste Land, not to mention

Ulysses, the finishing of

The Magic Mountain, and the beginning of

The Counterfeiters. The year 1922 is almost inexhaustible in all the arts" (426)

On Pound and prosody: "The general prosody of the 'teens and 'twenties had equally little to do with the practice of Yeats, Pound, and Eliot … and with the practice of the old conservatives. The general prosody was perhaps the weakest and least conscious in English since the dead poetry of the mid-sixteenth century. It ran, under various guises and doctrines, toward a combination of absolute doggerel and absolute expressionism. Ezra Pound was as responsible as anyone for this condition, not by the progress of his own work but by the procession of manifestoes which he promulgated by letter and print. His doctrine, however it may have promoted the incentive of writing, only got in the way of full work and when it got stronger, deeply damaged, though it never destroyed, his expressive powers" (427)

On "the ideographic method" and expressionism: "The procedure is very tempting, always, to get rid of what is behind one and what is ahead of one, neither by capitulation nor by mastery, but by declaring an arbitrary substitute. Then expression becomes immediate, which is good, and spontaneous, which is not; for spontaneity is the curse of poetry to at least the same degree that neologism is the curse of language. But the temptation is very deep; Art, as

Maritain says, Art bitten by poetry longs to be freed from reason, but so long as nothing is substituted for reason the longing is not fatal and may indeed promote a fresh and rejoicing sense of disorder, as

The Waste Land did, or a new underground for reason, as the work of Valéry and Mallarmé did" (428)

On Basic English: "What, should we get rid of our ignorance, of the very substance of our lives, merely in order to understand one another?" (428)

On the "heroization of the sensibility": "What [the modern poets] did was to make just enough of a prosody to heroize the sensibility and not quite enough to make a heroic statement. Just enough meter to make a patter, just enough rhyme to make a noise, just enough reason to make an argument; never enough of anything to bind together what came out of the reservoir of their extraordinary sensibility into possible poetry … This bad poetry is not worth reference in itself; it is here only to represent the condition of the language and the state of ambition in which an unusually large amount of good — or partly good — poetry got written" (428-429)

On flatness/prosiness: "Verse should be written, said Pound, not to the metronome but in the sequence of the musical phrase. The prose tradition alone produces flatness, inhibits song, and excludes behavior; and I see no sense in welcoming these disorders, as Eliot has done in parts of the Quartets and as Schwartz has done in all but his earliest work, as other and desirable forms of order. I do not refer to careless writing but to deliberate flatness; which is only the contemporary form of Georgian deliquescence" (429)

[

this opinion will become particularly interesting in the context of Ashbery, I think]

On solipsism and "the real world": "…it seems to have been an age when the sensibility took over much of the task of poetry. That is why we have created so many private worlds each claiming ascendancy over the real world about which nothing, or nearly nothing got said. That is why, too, Yeats and Eliot (though not Pound, except rarely) were almost alone able to express a version — an actual form — of the real world. In each the sensibility had other grounds than itself; the ground of beseeching, history, faith or momentum and the other ground, no less important to poetry, of prosody." (430)

Then there's a long section where RPB runs down all the various "schools" of Modernism (what Graves and Riding call "dead movements"), those not entirely assimilable to the traditions created by Yeats, Eliot or Pound. This is the fun part:

1. "the parallel Old-Timers' school, what we might call the school of Chaucer and the Ballad; think of Hardy, Housman, Robinson, and Frost … Reading them, we see why Pound does not occupy a first position, but a position on one side. The superlative metric of Pound may be a clue to their weakness but it would never furnish an understanding of their imperfect strength. Their work stands ready to infect the work of young men who have not yet found a form for their ambition and who can no longer, since they apprehend what has happened to it, heroize their sensibility. At least I should suppose there might be a coming race of poets who would want to reverse Maritain's phrase and say Art, bitten by reason, longs to be freed from poetry: from the spontaneous and the private and the calculated public worlds. There might be a race of poets, that is, who would woo the excited miracles of absolute statement, not as a refuge, but to get their work done" (432)

[

to me, this seems to presage a lot of the most accepted poetry today, in both America and Britain; what Ron Silliman calls the School of Quietude. More on this some other day, maybe.]

2. "the Apocalyptic or Violent school … Here is where we find the remains of Vachel Lindsay, the evangel of enthusiastic rebirth; Robinson Jeffers, the classical Freudian; Roy Campbell the animal, authoritarian evangel of anti-culture; Carl Sandburg, the bard of demagogic anti-culture; and of course others … All these stem poetically and emotionally from Whitman-Vates: and all are marked by ignorance, good will, solipsism, and evangelism … nor should we think of them even so briefly as more than false alarms if it were not for the two extraordinary talents that must be grouped with them … D.H. Lawrence and Hart Crane … Each is a blow in the face but neither can hit you twice" (433)

3. "another school of anti-intelligence … They got rid of too much of their reason, and as a result they effervesced rather than expressed, and what is left is flat. Nameless they shall be here; they belonged only to their principal journal

transition. What was wrong with them is clear when you see how weak is their imitation of Apollinaire, Aragon, Cocteau, Soupault [!], and how great their misunderstanding of Mallarmé, Rilke, Joyce, Kafka, and Pirandello: all men who longing to be freed from reason had a kind of bottom supply of it. Neither the English nor the Americans have ever been very good at this sort of thing. Let us say that we have not so much of reason that we can afford to lose any of it; we need it to make our nonsense real as well as genuine; and one would say that in this respect prosody was a form of reason" (433-434)

[

obviously, this will have renewed significance in the 60s with New York School et al.]

4. "the school of Donne into which the largest number of individual writers of good verse fall when shaken up and let settle … they are difficult in style, violent in their constructed emotions, private with actual secrecy in meaning. There is in their work a wrestling struggle toward statement, a struggle through paradox and irony … and the detritus of convictions. The statements are therefore impossible to make, but the effort to make them is exciting because genuine …" [

here he includes John Crowe Ransom, Allen Tate, John Wheelwright, William Empson and Hugh MacDiarmid]

"The general poetry at the center of our time takes the compact and studiable conceit of Donne with the direct eccentricity, vision, and private symbolism of Blake; takes from Hopkins the incalculable and unreliable freedom … of sprung rhythm, and the concentration camp of the single word; and from Emily Dickinson takes spontaneous snatched idiom and wooed accidental inductableness. It is a Court poetry, learned at its fingertips and full of a decorous willfulness called ambiguity. It is, in a mass society, a court poetry without a court" (434-435)

5. William Carlos Williams: "To him beauty is absolute and falls like the rain, like the dream of rain in a dry year. He is, if you like, the imagism of 1912 self-transcended. He is contact without tact; he is objectivism without objective … The neo-classicist and the neo-barbarian are alike in this: their vitality is without choice or purpose" (435)

6. Stevens/Moore/Cummings

"Each, so to speak, is full of syllables where [Yeats, Eliot and Pound] are full of words. Each is a kind of dandy, or connoisseur, a true mountebank of behavior made song … let us say they make an equilateral triangle of three styles hung like a pendant from the three major styles" (436)

a. Wallace Stevens is a dandy and a Platonist … You need an old dictionary and an old ear to get his beauty: as if he had to find an unfamiliar

name before the beauty of his perception could emerge; and it is along these lines that you have to think of the French symbolists' influence upon him. They taught Eliot the anti-poetic and the conversational style; Stevens they taught the archaic and the rhetorical; that is, Eliot and Stevens saw the one prosody running in opposite directions. But Stevens is in essence of a very old tradition, French and Platonic, working on a modern substance … He should have lived in the age of Pope; with his sensibility and his syllables he could have made rational statements with more beauty than that age was capable of. But as he is, he is 'the tranquil jewel in this confusion'" (436)

b. Marianne Moore "has written the most complex syllabic verse of our time: as if she brought French numbers to English rhythms with no principle of equivalence. But she is not the syllabist as dandy but as connoisseur; she is the syllabist of the actual, the metrist of the immediate marvel… There is a correspondence here to the coerced heightened perception (the forced close observation) in the painting of still-life. Poetry is to her, as she says, an imaginary garden with real toads in it. She knows all about the toads because she has imagined the garden; as you look suddenly everywhere there is the disengaged leap of a green or a brown toad, all warts, all soft, all leaping, all real. If there is not much other reality there, and there seldom is in a connoisseur's garden, you bring her, or ignore, the life she hasn't got just because what she has got is do real: you bring or ignore as with a shut-in whom you love" (436-437)

[

this is, incidentally, both one of the most eloquent and the most spectacularly condescending statements about MM ever made]

c. E.E. Cummings "is the child turned poet, the child with

that terrifying and incomplete dimension. Otherwise put, Cummings is the traditionalist who insists on the literal content of his tradition without re-understanding its sources: this is, of course, the easiest form of eccentricity and the most human form of fanaticism … He has too little a developed self ever to escape from it except waywardly, when you want either to console him or beat him … He was educated by Edmund Spenser, the English sonneteers, Keats, Swinburne, the funny-papers, and John Bunyan; but perhaps he was most educated by the things that were left out that would have gone to make a structured mind. All he knows is by enthusiasm, habit, and aversion. He refuses the job of the full intelligence, preferring intimacy with what he loves and contempt for what he hates; and he accepts what love and hatred give as if they made all the music of a full mind … if he were not part of a going concern larger than he, he would be nothing. Here again is a case where prosody is an instrument of reason. Like the wilder currencies in the age of Veluta (or like the serried marks of Hitler [!!!]) Cummings' experimental typography depends on the constant presence of the standard it departs from and would be worthless if not measured against it" (437-438)

[

seems like some of these ideas — or prejudices, if you like — could be usefully applied to Kenneth Koch]

Blackmur finishes up by assessing "the further development and release, still inchoate to these observations, of

the doomed school of Auden about 1930" with its "deliberate approach to doggerel through Skelton, the Ballads, the immediate situation, and the multi-valenced distrust of self combined to produce the new flat style" (438-439): again, this suspicion of "flatness," and an interesting offhand use of the rhetoric of "doomedness" so often applied to the poets of 1890s (which, as RPB must be thinking of, produced Yeats). He also looks toward "

the generation born between 1913 and 1918: Shapiro, Barker, Schwartz, Thomas, Berryman, Manifold, Lowell, Betjeman, Meredith, and Reed" (I must admit I have no idea who half these people are). Solemnly passing the torch to these promising whippersnappers, Blackmur delivers the New Critic's version of "you kids today don't know how good you've got it": "they have the enormous advantage over their predecessors that there is an idiom ready for them to develop according to their own needs" (439). So this is what it has come to, Modernism is "an idiom," and no longer anything like a movement, or even a set of loosely concatenatable authors and texts. "We might have a great age out of them yet," he reckons, but if they do succeed it will be because they keep ploughing the same furrow as the Big Three (or at least their equilateral pendant): "[t]hey have more than a chance — it is half done for them — to develop out of personality the most objective of all creations, the least arbitrary and spontaneous, a style."

Countdown to "

arbitrary and spontaneous" begins now.