Friday, September 28, 2007

Thursday, September 27, 2007

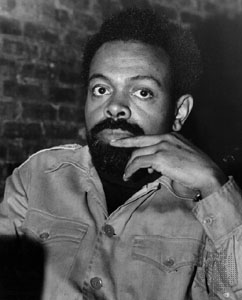

Keeping Up with LeRoi Jones

If one wanted a pocket history of late-fifties American avant-garde poetry that was under fifty pages and all by one author, one could do worse than to read LeRoi Jones' 1961 Preface to a Twenty-Volume Suicide Note. A teasing little note at the beginning of the book states that "these poems cover a period from 1957 until 1960 … I have arranged the book in as strict a chronological order as I could manage … for reasons best known to other young (?) poets" (parenthetical question mark Jones's). What this refers to I'm not entirely clear, but it's certainly true that Preface to a Twenty-Volume Suicide Note, more even than most books of poetry so arranged, is clarified enormously by proceeding chronologically. Jones covered a lot of distance in those three years, ending up, on the surface at least, at almost the diametrically opposite point to where he began.

If one wanted a pocket history of late-fifties American avant-garde poetry that was under fifty pages and all by one author, one could do worse than to read LeRoi Jones' 1961 Preface to a Twenty-Volume Suicide Note. A teasing little note at the beginning of the book states that "these poems cover a period from 1957 until 1960 … I have arranged the book in as strict a chronological order as I could manage … for reasons best known to other young (?) poets" (parenthetical question mark Jones's). What this refers to I'm not entirely clear, but it's certainly true that Preface to a Twenty-Volume Suicide Note, more even than most books of poetry so arranged, is clarified enormously by proceeding chronologically. Jones covered a lot of distance in those three years, ending up, on the surface at least, at almost the diametrically opposite point to where he began.The early poems have a casualness and humor that brings to mind the Beats and Frank O'Hara (all of whom were personal friends of Jones, and published by his Totem Press and Yugen magazine), as well as bearing plenty of traces of E.E. Cummings' easygoing satire. "Hymn for Lanie Poo," the second poem in the book, is a good example: a record of a black man's experiences in white urban bohemia, it features a provocative epigraph from Rimbaud ("Vous etes de faux Négres") and has references to John Coltrane, offhand travesties of academic "high" culture ("Read Garmanda's book, '14 Tribes of / Ambiguity,' didn't like it") and a generally breezy tone. Except for the heightened racial consciousness and occasional dips into a more Gothic register ("Beware the evil sun… / turn you black // crawl your eyeballs // rot your teeth"), this could be a late-fifties poem by O'Hara.

But Jones (like O'Hara himself, in fact) eventually becomes interested not just in expressing his personality but in critiquing it, a process which begins with the (great) sixth poem, "Look For You Yesterday, Here You Come Today." It begins: "Part of my charm: / envious blues feeling / separation of church & state / grim calls from drunk debutantes," the beginning of a poem-long anatomy of Jones' personality and lifestyle which is intricately bound up, not just with his status as a black man in a mostly white subculture, but with his role as literary editor as well:

terrible poems come in the mail. Descriptions of celibate parties

torn trousers: Great Poets dying

with their strophes on. & me

incapable of a simple straightforward

anger.

It's so diffuse

being alive. (15)

From there, Jones goes on to muse O'Hara-ishly about not being a painter, quote O'Hara himself on the value of quietism, contra Kerouac ("Frank walked off the stage, singing / 'My silence is as important as Jack's incessant yatter'"), associate his thoughts with Baudelaire's ("All these thots / are Flowers Of Evil"), get lost in a nostalgic reverie ("What has happened to box tops?"), and finally imagine his own death ("F. Scott Charon / will soon be glad-handing me / like a legionaire / My silver bullets all gone / My black mask trampled in the dust"). Thus the interior movement of this one poem anticipates the movement of Jones' development on the level of oeuvre.

What happens there is unexpected. As I read it, it entails a move away from O'Hara towards an engagement with the canonical texts of High Modernism: in particular, with exactly the quality of Modernism that poets like O'Hara, Ginsberg, Ashbery and Koch were most concerned to protest, its thoroughgoing depressiveness. Two poems in the middle of the book, "Way Out West" and "The Bridge," initiate a new phase in Jones' poetry by imitating and investigating what I'm going to call here the mode of "FUBAR Modernism," the sense of an entire environment gone to pot that in Eliot expresses itself elegiacally and, often through the use of the affective fallacy, lyrically as well. This return to Eliot, who Koch would later call "the Great Dictator / Of literature" (and not even exactly a return: let's keep in mind that Eliot was still alive in 1961, and if he was out of fashion with the avant-garde he was, in many ways, at the peak of his cultural power in the literary mainstream), is pretty surprising in a fellow-traveler of the Beats, Black Mountain and New York School, none of whom had much use for Eliot, preferring Pound and Williams if they had to have Modernist forebears at all.

I feel I could make a case for Eliot's pervasiveness throughout the whole second half of Preface to a Twenty-Volume Suicide Note, but for simplicity's sake I'll stick to the two poems aforementioned. Here's "Way Out West" in its entirety:

As simple an act

as opening the eyes. Merely

coming into things by degrees.

Morning: some tear is broken

on the wooden stairs

of my lady's eyes. Profusions

of green. The leaves. Their

constant prehensions. Like old

junkies on Sheridan Square, eyes

cold and round. There is a song

Nat Cole sings … This city

& the intricate disorder

of the seasons.

Unable to mention

something as abstract as time.

Even so, (bowing low in thick

smoke from cheap incense; all

kinds questions filling the mouth,

till you suffocate & fall dead

to opulent carpet.) Even so,

shadows will creep over your flesh

& hide your disorder, your lies.

There are unattractive wild ferns

outside the window

where the cats hide. They yowl

from there at nights. In heat

& bleeding on my tulips.

Steel bells, like the evil

unwashed Sphinx, towing in the twilight.

Childless old murderers, for centuries

with musty eyes.

I am distressed. Thinking

of the seasons, how they pass,

how I pass, my very youth, the

ripe sweet of my life; drained off…

Like giant rhesus monkeys;

picking their skulls,

with ingenious cruelty

sucking out the brains.

No use for beauty

collapsed, with moldy breath

done in. Insidious weight

of cankered dreams. Tiresias'

weathered cock.

Walking into the sea, shells

caught in the hair. Coarse

waves tearing the tongue.

Closing the eyes. As

simple an act. You float (24)

That the poem describes the contemplation of suicide should be obvious (even if Jones' book title didn't nudge us toward that reading). But it also narrates the passing of a day, beginning with "opening the eyes" and ending with "closing" them, though both are understood as "simple … act[s]" that contain within them the possibility of death, which is just as easy to bring on as wakefulness or sleep. As in Eliot, there is a constant toggling between dramatic or autobiographical details and purer image-making. There is also a tension between lyric and jeremiad, if we take the former to be the questioning of the self and the latter to be the questioning of the world. The textbook lyrical move of describing his "lady's eyes" leads him first to the natural world ("The / leaves. Their constant prehensions") and then to a corruption of it, as those eyes are in turn compared to "old / junkies on Sheridan Square" in a way that gives a wider characterization of the urban landscape in which our narrator dwells, a landscape which, as in Eliot, undermines the lyric impulse while paradoxically strengthening its effects (cf. Kant on disgust). The speaker, thrown once again into this sordid world, thinks of but does not quote from one of its more pleasant manifestations, a "Nat [King] Cole" song (an obvious update of the music hall numbers Eliot inserted into The Waste Land), and then free-associates across an ellipsis about "[t]his city / & the intricate disorder / of the seasons": an intricate disorder which recalls that which "breeds lilacs out of the dead land," the "stony rubbish" of "The Burial of the Dead." (I take it as significant that there is natural growth in Eliot's poem: it just appears as perverse, unnatural.) Writing a poem in what he sees as a waste land, but after Eliot, and after the avant-garde reaction against Eliot, Jones feels unentitled to the later Eliot's devices for coping with such misery: he is "[u]nable to mention / something as abstract as time" as in the redemptive Four Quartets (though of course Jones, in asserting this, has just mentioned it). Moving a little faster, we find "creep[ing]" "shadows," a personal "intricate disorder" ("your disorder") to match that of the city's, a dip into the rhetoric of pastoral elegy ("Thinking / of the seasons, how they pass, / how I pass, my very youth, the / ripe sweet of my life; drained off…"), horrible visceral images of the kind Eliot's early poetry is full of ("Childless old murderers," "giant rhesus monkeys") and then a final double echo, first of The Waste Land ("No use for beauty / collapsed … Tiresias' / weathered cock") and then, climactically, of "Prufrock" ("Walking into the sea, shells / caught in the hair. Coarse / waves tearing the tongue"): walk, sea, hair, drowning.

The next poem in the book, "The Bridge," takes up a different High Modernist author, one less eminent and influential than Eliot but perhaps even better as a symbol of the FUBAR aesthetic, since he actually killed himself: Hart Crane. The poem is not formally much like Crane, but it pays him unmistakable homage in its title and in its imagery.

I have forgotten the head

of where I am. Here at the bridge. 2

bars, down the street, seeming

to wrap themselves around my fingers, the day,

screams in me: pitiful like a little girl

you sense will be dead before the winter

is over.

I can't see the bridge now, I've past

it, its shadow, we drove through, headed out

along the cold insensitive roads to what

we wanted to call "ourselves."

"How does the bridge go?"

Here the bridge is also a musical bridge, and the poem can be understood as written from the perspective of a jazz musician. This realization renders the first strophe almost Metaphysical in its playfulness, with existential confusion figured as losing one's way in a song ("I have forgotten the head / of where I am") and "bars" meaning both measures of time in music and places where you drink alcohol, both of which are felt as mysteriously constricting ("seeming to wrap themselves around my fingers"). But music really appeals to Jones as a symbol of the unfreezable flow of time, a forward-rushing movement that cannot be seized at any one moment without losing its integrity: "The changes are difficult, when / you hear them, & know they are all in you, the chords // of your disorder meddle with your would be disguises." The obvious play is on "changes" as both chord changes and historical changes, both of which are "difficult" in the sense of jarring but which are felt as corresponding to some innate and inchoate need of the self, "your disorder" as opposed to "your would be disguises." My claim, a little bit of a stretch maybe, is that it's not just free jazz — and the postwar, postmodern moment associated with it — that Jones is talking about here, but also Crane's The Bridge, and Modernism. This has been left behind for what is already, by the late 50s, observable on the horizon as the coming of Confessionalism, which Jones presciently sees as abandoning monumental expression to travel down "the cold insensitive roads to what / we wanted to call 'ourselves.'"

The second half of the poem starts: "(Late feeling)," indicating a kind of postscript I suppose, the morning after the jazz performance maybe, but also continuing the theme of time, and of belatedness. It continues:

Way down till it barely, after that rush of

wind & odor reflected from hills you have forgotten the color

when you touch the water, & it closes, slowly, around your head.

Another image of immersion, death by water, suicide. But:

The bridge will be behind you, that music you know, that place,

you feel when you look up to say, it is me, & I have forgotten,

all the things, you told me to love, to try to understand, the

bridge will stand, high up in the clouds & the light, & you,

(when you have let the song run out) will be sliding through

unmentionable black. (26)

"The bridge will be behind you": literally in time (because the performance is over) but also figuratively in memory (because the forward-looking avant-garde is leaving The Bridge behind, and The Waste Land, or so they think). I read the passage, then, as expressing a certain melancholy for the moment of 20s/30s Modernism — a time when, arguably, jazz and avant-garde writing were more closely socially associated; in any case, a monumental timelessness ("the bridge will stand") placed in opposition to contemporary triviality, "all the things, you told me to love, to try to understand" (the pop cultural detritus celebrated in O'Hara's work, and in Preface's first six poems). Without the fixity and permanence of "the bridge" (a bridge between white and black experience? a testament to the potential of communal, human making?), the speaker of the poem is doomed to slide into solipsism, to racial and social isolation, "unmentionable black."

I guess what interests me most about this reading of Jones (which could be totally off the mark: I should admit I don't know almost any of his later, more militant work) is that it really fucks with the historical narrative that sees postwar poets, particularly ones with political leanings, rebelling against the High Modernist aesthetic of Eliot, Pound, Crane, etc. I'd argue that this is truer of essentially apolitical poets like Robert Lowell and (gulp) John Ashbery, who refuse High Modernism for affective reasons — it's not the mood, the tone they want to project — rather than because they see it is ideologically or communicatively faulty. This doesn't have to be a question of competing metaphysics, or its objectification ("poetics"), it's just rhetoric: the language of and The Waste Land and The Bridge is more "political" — i.e. more strident, stirring, closer to agitprop and soapbox speeches — than the language of Life Studies and Self-Portrait in a Convex Mirror. Even if "the personal is the political," the persons involved have to speak to and convince each other: as Eliot puts it in Sweeney Agonistes, "I gotta use words when I talk to you."

For the trajectory of influence in Preface to a Twenty-Volume Suicide Note is so clearly from O'Hara to Eliot, and not the other way around: that is, from personality to impersonality. And it is exactly personality, in O'Hara's sense, which is rejected by Jones as hegemonic, pedagogical, and totalizing ("all the things, you told me to love, to try to understand"). The mode of Eliot (and the example of Crane), on the other hand, offer him a different kind of expression.

Wednesday, September 26, 2007

Tuesday, September 25, 2007

Translatedness

comes into American poetry in a big way in, or at least by, the mid-1950s. By this I mean not just the foreign but the obviously translated, the slightly awkward, the conspicuously non-American and non-English. Exhibit A: Frank O'Hara's Meditations in an Emergency (1957), particularly the poems "The Hunter" and "On Looking at La Grand Jatte, The Czar Wept Anew":

comes into American poetry in a big way in, or at least by, the mid-1950s. By this I mean not just the foreign but the obviously translated, the slightly awkward, the conspicuously non-American and non-English. Exhibit A: Frank O'Hara's Meditations in an Emergency (1957), particularly the poems "The Hunter" and "On Looking at La Grand Jatte, The Czar Wept Anew":"He went to strange hills where

the stones were still warm from feet,

and then on and on. There were clouds

at his knees, his eyelashes

has grown thick from the colds,

as the fur of the bear does

in winter. Perhaps, he thought, I am

asleep, but he did not freeze to death." (CP, 167)

"He cannot, after all, walk up the wall. The skylight

is sealed. For why? for a change in the season,

for a refurbishing of the house. He wonders if,

when the music is over, he should not take down

the drapes, take up the rug, and join his friends

out there near the lake, right here beside the lake!

'O friends of my heart!'" (CP, 63)

The tone in these passages is odd but not too odd, less formally idiosyncratic than idiomatically off. A phrase like "the fur of the bear" could easily be made to sound less ridiculous (probably not O'Hara's purpose in this poem which, like so many others, verges on camp mockery) but the juxtaposition of images (frozen eyelashes and bear's fur) wouldn't be as striking if it were smoothed out that way. Even more noticeably, "For why?" is not exactly English: it's the sort of endearing mistake non-native speakers make all the time, but which in a poem achieves an uncanny effect unavailable to "Why?" or "What for?" The sense I get is that O'Hara is tentatively approaching, through parody, a style that in the 70s and 80s actually becomes a mainstream mode of American poetry, with Deep Image, Charles Simic et al: a style whose hallmark is the combination of a semi-colloquial simplicity coupled with a more formal-seeming resistance to contractions ("I am" not "I'm," "should not" not "shouldn't").

This is happening in other avant-garde work of the time, too. Exhibit B: Jack Spicer's After Lorca (1956), which purports to be an actual volume of translations though, as the ghost of Lorca writes in his introduction, "Mr. Spicer seems to derive pleasure in inserting and substituting one or two words which completely change the mood and often the meaning of the poem as I had written it" and "there are an almost equal number of poems that I did not write at all (one supposes that they must be his) executed in a somewhat fanciful imitation of my earlier style" (11). The poems themselves are good but, to me, unremarkable; however,

This is happening in other avant-garde work of the time, too. Exhibit B: Jack Spicer's After Lorca (1956), which purports to be an actual volume of translations though, as the ghost of Lorca writes in his introduction, "Mr. Spicer seems to derive pleasure in inserting and substituting one or two words which completely change the mood and often the meaning of the poem as I had written it" and "there are an almost equal number of poems that I did not write at all (one supposes that they must be his) executed in a somewhat fanciful imitation of my earlier style" (11). The poems themselves are good but, to me, unremarkable; however,they are interspersed with fascinating micro-manifestoes, in the manner of Williams' Spring and All, which explicitly throw over Modernist precepts by declaring that the specific words of the poem, and whatever intricate changes are wrought on them, do not matter, since all such tinkering is doomed to be lost in translation anyway. Here's one of the more provocative moments:

Most of my friends like words too well. They set them under the blinding light of the poem and try to extract every possible connotation from each of them, every temporary pun, every direct or indirect connection — as if a word could become an object by mere addition of consequences. Others pick up words from the streets, from their bars, from their offices and display them proudly in their poems as if they were shouting, "See what I have collected from the American language. Look at my butterflies, my stamps, my old shoes!" What does one do with all this crap?

Words are what sticks to the real. We use them to push the real, to drag the real into the poem. They are what we hold on with, nothing else. They are as valuable in themselves as rope with nothing to be tied to. (Collected Books of Jack Spicer, 25)

Note that Spicer's reasons for writing in this style is not metaphysical but rhetorical: it's not that he values "the real" in and of itself, but that he wants his poems to last, and to travel. Haunting the first of these paragraphs is a judgment that two of the most influential strains of Anglo-American Modernism in the first half of the 20th century — the "blinding light" school of Eliot and Empson and the "stamp collection" school of Moore and Pound — are not aging, or translating, well. (This might also be the place to note that Spicer, like O'Hara, comes to this partial rejection of Modernist aesthetics through the oblique channels of camp. After Lorca is a very funny book.)

Final question: is this kind of thing really new? Though imitation of non-English sources had been going on for a long time (at least since Whitman, and probably earlier), most of those give the impression that the writer read those sources in the original: they imitate them as they were familiar with the work on its own terms, trying to replicate some quality in the language. Or, more rarely, they just ignore the poem's original linguistic presentation and engage them solely on the level of theme. But part of what interests Spicer and O'Hara, in different ways and for different reasons of course, is the style of translation itself, and the then-novel fact that they're even able to read poetry so geographically and linguistically remote from them as if it were written in English. (To my mind, this also distinguishes what they're doing from Pound's material reminders to the reader of his work's translatedness — "lie quiet Divus" and the like — which still imply a first-order encounter with the original text, won through the poet's own attention and labor.)

That's all I got for now. But the magazine New World Writing, which appeared from 1952 to 1959 and which O'Hara mentions in a later poem (he buys it in order "to see what the poets in Ghana are doing these days"), might be an interesting place to look in pursuing this question.

Monday, September 24, 2007

"Dare not decline" - costs of going local

"Poet appointed dare not decline

to walk among the bogus"

So begins the second section of Basil Bunting's Briggflatts, and it sets an injunction the poet cannot keep precisely because "who appointed him?" is the next question. "Decline" - which by the poem's 1966 publication is a deeply troubled term for national devolution in post-War, post-imperial English national topology - can mean two things here: "don't refuse to walk among the bogus" or "don't descend down among the bogus". Either a self-harming injunction to wallow or a self-deceiving presumption of authenticity in a world dirtily without.

This strikes me as paradigmatic of the poet's choices who would attempt epic, even the modernist/Poundian "poem including history", when he (or she) is confronted with a national history that has both shrunk to rocky Saxon particularity and exploded to a global dialogue of plural histories. The rich and gorgeous language of the first section of Briggflatts uncovers a deep and local continuity that could be the epic poet's material (and has Pound's version of and use in the Cantos of "The Seafarer" as a predecessor): "By such rocks/ men killed Bloodaxe." It can be carved in stone and, as in section V's echo of Four Quartets, "Then is diffused in Now" (echo of the Quartets, but diminished -- not about presence and chronological fusion so much as "diffusion", dispersal, weakening).

The poem, called an "autobiography," includes in the second section a reference to Bunting's time as a spy for the British, who "decodes/ thunder, scans/ porridge bubbling, pipes clanking". Eliot, secretive but no spy, could once simply hear what the thunder said. Left the porridge alone. Bunting, in this role among the bogus, must detail the impoverished surround, laying "sick, self-maimed, self-hating,/ obstinate, mating/ beauty with squalor to beget lines still-born." The local, which is the ground of the poem and its primary linguistic audience, forms a substrate of filth rather than a solid ground in which to grow a regional epic. The poem begins to clog with fecal matter, which composts any number of rotting decapitated heads (as the poem's opening describes, "Decay thrusts the blade,/ wheat stands in excrement/ trembling"). As Bunting writes in section IV, "Today's posts are piles to drive into the quaggy past/ on which impermanent palaces balance."

The figure of the still-born, or as another possibility of this "mating", the monstrous is the abiding concern of the poem, itself then a half-product of a region (with the potential for epic) and of the deaths that register that region's deep history (with their potential for elegy). The tomb carved in section one is for the deceased child of the young couple who ride with the mason across Rawthey, and the poem gives gory details about the bestiality that brought us the Minotaur.

I'd like to explore the poem's conjoined topoi of monstrosity and hybridity in the formation of subjective declension. But I'll leave that for now and make a note about the "still-born" as a description of both poem and nation. Though the "sun rises on an acknowledged land" the poem ends with a coda that brings this diurnal recognition into the symbolic sweep of a completed elegiac movement, initiated in such an extended fashion as to make it hard to perceive until *blammo* he's playing off the end of "Lycidas". In the Coda,

A strong song tows

us, long earsick.

Blind, we follow

rain slant, spray flick

to fields we do not know.

Lycidas has its own coda -- its last eight lines zoom out to the third person to describe how "thus sang the uncouth swain" all that had come before. The gesture toward "fresh woods, and pastures new" complete the consolatory purpose of the elegy and declare closed the literary apprenticeship of the lyric speaker, who thereby promises and indeed begins to perform the consummation of his voice in writing the great work (the last 8 lines = one ottava rima stanza of italian epic). In Bunting, the coda works in the opposite direction, marshalling community in blind servile following of the song, and ends with a reworking of the "pastures new" from promise to disillusionment:

Where we are who knows

of kings who sup

while day fails? Who,

swinging his axe

to fell kings, guesses

where we go?

It's Lycidas rewritten with a proleptic view of the heads that would roll in the coming years, both the need for protestant revolution and an acknowledgment of its costs (esp. in post-industrial -- notice how these poems of local epic or thwarted epic have so much interest in work, in craft).

Oh, i'm getting tired of writing this. Something something. The political economy of the commonweal (see the etymology of "bogus" in the OED, as it emerges as a major point of reactionary possibility in English late-mod. epics in this period (see also Hill's Mercian Hymns, lots of Hughes's poems I think) and as a grounding moment in the portraits of community and region that are all over the place in America at this point (Paterson, Howl, Brooks's sketches of Bronzeville, Hughes's "Portrait of a Dream Deferred").

Sorry to cop out but I got other work to do. May come back and edit this eventually. Could continue in the comments, since i'm sure i haven't made myself very clear.

Labels:

Bunting,

Davie,

Eliot,

Pound,

Regionalism,

William Carlos Williams

Howl, New Jersey, Holla

Have either of you looked at a little book called The Poem that Changed America: "Howl" Fifty Years Later? Silly title, I know, but it's actually pretty useful. The collection is edited by Jason Shinder, Ginsberg's personal assistant from the late 70s on, and his introduction is kind of embarrassingly idolatrous and not very well-written. But the volume does bring together a number of interesting reactions to "Howl" (by, among others, Amiri Baraka, Marjorie Perloff (who argues that Ginsberg is a direct inheritor of Modernism [OK, fine, whatever] and that "Howl" is really about WWII [more interesting]), Billy Collins (!), John Cage, and Rick Moody) as well as including a facsimile of the original mimeographed edition, which "costed [sic] $10.00 typed by poet Robert Creely [sic] dittoed by Martha Rexroth transported by me to the hands of Robert Lavigne [sic] in exchange for several drawings," according to Ginsberg's inscription. (Doesn't $10 seem like kind of a lot of money for 1956? Seems like one could do a Lawrence Rainey-esque analysis of the economics of this first presentation.)

Have either of you looked at a little book called The Poem that Changed America: "Howl" Fifty Years Later? Silly title, I know, but it's actually pretty useful. The collection is edited by Jason Shinder, Ginsberg's personal assistant from the late 70s on, and his introduction is kind of embarrassingly idolatrous and not very well-written. But the volume does bring together a number of interesting reactions to "Howl" (by, among others, Amiri Baraka, Marjorie Perloff (who argues that Ginsberg is a direct inheritor of Modernism [OK, fine, whatever] and that "Howl" is really about WWII [more interesting]), Billy Collins (!), John Cage, and Rick Moody) as well as including a facsimile of the original mimeographed edition, which "costed [sic] $10.00 typed by poet Robert Creely [sic] dittoed by Martha Rexroth transported by me to the hands of Robert Lavigne [sic] in exchange for several drawings," according to Ginsberg's inscription. (Doesn't $10 seem like kind of a lot of money for 1956? Seems like one could do a Lawrence Rainey-esque analysis of the economics of this first presentation.)A couple of remarks about the poem itself: has anyone written on the possible influence of W.H. Auden on Ginsberg? Auden is mentioned in Shinder's preface as one of Ginsberg's "'enemies'," but also an "eternal presence": I don't know much about their personal relationship. But on this reading I notice quite a few touches which seem Audenesque; for one, the unexpected dropping and adding of definite articles (examples include "the drear light of Zoo" and "the last fantastic book thrown out of the tenement window"). This is something Auden does a lot, and I think the effect in his poems is usually to either particularize or universalize the rhetorical situation of any given poem: kind of a Zoom-In/Zoom-Out effect. In "Howl," Ginsberg utilizes this to keep the reader involved on a macrosociological level ("this is an important poem: it's about a generation, it's about a nation, it's about history") and on a more micro-, affective/emotional level ("this is about the author, his friends, his mother, or me"). It's a technique Whitman uses too, of course, but Ginsberg's interest in including shabby, sordid or ironic details which temporarily undercut the grandeur of the macro-phrases (e.g. "in beards and shorts with big pacifist eyes sexy in their dark skin passing out incomprehensible leaflets"; compare "Spain 1937") is closer to (early) Auden, I think.

Second idea: Ginsberg's insistent return to New Jersey place names ("Paterson," "Newark," "the filthy Passaic," etc.), among, admittedly, a lot of other place names, has to be understood, in its historical context, as a very complicated rhetorical move. Because New Jersey was not just where Ginsberg was from, and thus a signifier of the "real" or the "autobiographical," but also, by the mid-1950s, a landscape that was newly literary, thanks to the ecstatic critical reception of William Carlos Williams' still-in-progress Paterson. As Perloff points out her chapter on him in The Poetics of Indeterminacy, the publication of Paterson had finally secured a major reputation for Williams, long considered a marginal figure of the Modernist movement. Thus Paterson, which ten years earlier would have been fairly meaningless as a literary signifier, now evokes a whole complex of ideas about Modernism and American poetry that Ginsberg slyly insists upon. (And WCW also wrote the introduction to Howl's first commercial edition, as Adrienne pointed out months ago.)

Anyway, it's interesting to think of the symbolic capital that New Jersey acquires in this period, as the breeding ground of the only ideologically correct,* homegrown version of High Modernism (Williams') as well as the most incendiary updating/challenging of the academic version of Modernism: significantly a humble state, in proximity to a great metropolis but not containing it, a place synonymous with the simple, homely and plain, which also just happens to be the site of some of the worst industrial exploitation and ecological spoilage in the entire country. This is quite a different pole to orient us than London or New York, and the attitude of its writers to it is also significantly different: sure, it's a waste land, they tell us, but it's our waste land, and we like it that way. And this in turn might have something to do with the remarks by Leslie Fiedler that Adrienne just posted, about the American mediation (some would say adulteration) of Modernism through regionalism. But I'm getting hungry, so I'd better stop here and drag myself through some Brooklyn streets to go looking for a sandwich fix.

* If you ignore the Communism.

In literary love

Below is the basic argument of Leslie Fiedler's essay War, Exile, and the Death of Honor from his book Wating For the End: A portrait of Twentieth-Century American Literature and Its Writers". I want his brain.

"It is tempting to think of the practice of our writers of the Twenties as representing a decisive disavowal of the temptations of avant-gardism, and, in a sense, this is true; but it is not true enough. Hemingway and Gertrude Stein may have become at last, symbolically as well as personally, enemies; yet the example of her war on syntax and coherence made him to the end a more insidious subverter of common speech than the readers of Life magazine could ever permit themselves to recognize even if they were capable of doing so. And however stubbornly Faulkner insisted on reinventing stream-of-consciousness in his own home-made terms, the experiments of Joyce surely inspired the effort. The ostensible rejection and the abiding nostalgia, the pride and shame of the generation of the Twenties in its encounter with Europe, is, in fact, the reaction of the tourist, the provincial tourist. It matters little whether the writers played abroad for a long time like Fitzgerald, or retreated immediately to their home towns like Faulkner, or kept seeking on foreign continents images of Montana and Upper Michigan like Hemingway--the writers who came of age in WWI remained what they were to begin with: country boys perpetually astonished at meeting the Big City and the Great World, provincials forever surprised to discover themselves in London or Paris or Antibes, and afterward dazzled to remember that they had ever been in such improbable places."

Fiedler than goes on to recount the long tradition of American writers abroad (From Franklin to Irving, Hawthorne and Melville to Baldwin and Burroughs) "It is, indeed, astonishing how many especially American fictions were conceived or actually executed abroad from Rip Van Winkle through the Leather Stocking Tales, the Marble Faun of Hawthorne, Twain's Pudd'nhead Wilson to Fitzgerald's Tender Is the Night and The Sun Also Rises of Hemingway.

"Such novels of exile and return reflect the deepest truth, the mythical truth of the experience of Americans abroad, a truth of art which life does not always succeed in imitating, though it is one to which it aspires. TS Eliot may never go back to St. Louis to live out his declining years, while Pound, released from captivity in the States, seems set on dying in Rapallo. And if Rapallo looks, as Karl Shapiro has somewhere observed, just like Santa Barbara, California, that is just one of those irrelevant jokes which history plays on us all"

He goes on to flush out this theme of exile and return. "Even Eliot, Anglo-Catholic and Royalist, returns home in his imagination, making a pilgrimage in the Four Quartets not only to New England, but even, less forseeably, to Huck Finn's Mississippi, beside which he was born."

"In Paris, obviously different from the dream of Paris, the American discovers he can bear Kansas City, which he began knowing was different from all dreams of it; and this is worth his fare plus whatever heartache he pays as surtax."

"And though there is a sense in which the anti-war novel is merely a late sub-variety of the international theme (and another in which it is a sub-genre of the class-struggle book), we are compelled how to recognize it as the greatest and most characteristic literary invention of the Twenties."

"But pacifism, too, was a fiction of WWII, which saw thousands of young men, who earlier had risen in schools and colleges to swear that they would never bear arms, march off to battle--as often as not with copies of anti-warbooks in their packs. Those books were real enough, like the passion that prompted them, and the zeal with which they were read; only the promises were illusory."

"We inhabit for the first time a world in which men begin wars knowing that their avowed ends will not be accomplished, a world in which it is more and more difficult to believe that the conflicts we cannot avert are in any sense justified. And in such a world, the draft dodger, the malingerer, the goldbrick, the crap-out, all who make what Hemingway was the first to call 'a separate peace,' all who somehow survive the bombardment of shells and cant, become a new kind of anti-heroic hero. And it is precisely such sad sacks, such refugees from honor and glory, who returned to American to beget or become the generation of the Thirties."

"It is tempting to think of the practice of our writers of the Twenties as representing a decisive disavowal of the temptations of avant-gardism, and, in a sense, this is true; but it is not true enough. Hemingway and Gertrude Stein may have become at last, symbolically as well as personally, enemies; yet the example of her war on syntax and coherence made him to the end a more insidious subverter of common speech than the readers of Life magazine could ever permit themselves to recognize even if they were capable of doing so. And however stubbornly Faulkner insisted on reinventing stream-of-consciousness in his own home-made terms, the experiments of Joyce surely inspired the effort. The ostensible rejection and the abiding nostalgia, the pride and shame of the generation of the Twenties in its encounter with Europe, is, in fact, the reaction of the tourist, the provincial tourist. It matters little whether the writers played abroad for a long time like Fitzgerald, or retreated immediately to their home towns like Faulkner, or kept seeking on foreign continents images of Montana and Upper Michigan like Hemingway--the writers who came of age in WWI remained what they were to begin with: country boys perpetually astonished at meeting the Big City and the Great World, provincials forever surprised to discover themselves in London or Paris or Antibes, and afterward dazzled to remember that they had ever been in such improbable places."

Fiedler than goes on to recount the long tradition of American writers abroad (From Franklin to Irving, Hawthorne and Melville to Baldwin and Burroughs) "It is, indeed, astonishing how many especially American fictions were conceived or actually executed abroad from Rip Van Winkle through the Leather Stocking Tales, the Marble Faun of Hawthorne, Twain's Pudd'nhead Wilson to Fitzgerald's Tender Is the Night and The Sun Also Rises of Hemingway.

"Such novels of exile and return reflect the deepest truth, the mythical truth of the experience of Americans abroad, a truth of art which life does not always succeed in imitating, though it is one to which it aspires. TS Eliot may never go back to St. Louis to live out his declining years, while Pound, released from captivity in the States, seems set on dying in Rapallo. And if Rapallo looks, as Karl Shapiro has somewhere observed, just like Santa Barbara, California, that is just one of those irrelevant jokes which history plays on us all"

He goes on to flush out this theme of exile and return. "Even Eliot, Anglo-Catholic and Royalist, returns home in his imagination, making a pilgrimage in the Four Quartets not only to New England, but even, less forseeably, to Huck Finn's Mississippi, beside which he was born."

"In Paris, obviously different from the dream of Paris, the American discovers he can bear Kansas City, which he began knowing was different from all dreams of it; and this is worth his fare plus whatever heartache he pays as surtax."

"And though there is a sense in which the anti-war novel is merely a late sub-variety of the international theme (and another in which it is a sub-genre of the class-struggle book), we are compelled how to recognize it as the greatest and most characteristic literary invention of the Twenties."

"But pacifism, too, was a fiction of WWII, which saw thousands of young men, who earlier had risen in schools and colleges to swear that they would never bear arms, march off to battle--as often as not with copies of anti-warbooks in their packs. Those books were real enough, like the passion that prompted them, and the zeal with which they were read; only the promises were illusory."

"We inhabit for the first time a world in which men begin wars knowing that their avowed ends will not be accomplished, a world in which it is more and more difficult to believe that the conflicts we cannot avert are in any sense justified. And in such a world, the draft dodger, the malingerer, the goldbrick, the crap-out, all who make what Hemingway was the first to call 'a separate peace,' all who somehow survive the bombardment of shells and cant, become a new kind of anti-heroic hero. And it is precisely such sad sacks, such refugees from honor and glory, who returned to American to beget or become the generation of the Thirties."

Sunday, September 23, 2007

Theory vs. Theory

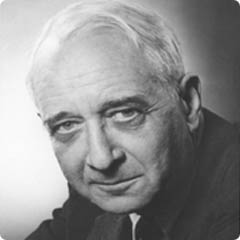

Remember when Jeremy was talking in our seminar about the need at Princeton for a course that traces the history of literary theory from Russian Formalism through French structuralism/poststructuralism and American deconstruction and into its current phase of disciplinary/international diaspora? Well, I just came across such a history, in miniature, and admittedly from a partisan position, by Raymond Williams. It's taken from the appendix of The Politics of Modernism, which is the transcript of a public conversation between Williams and Edward Said in 1986. Whether you agree or not with the polemical points of Williams' narrative (and probably none of us really know enough about the subject to be sure about that yet; certainly I don't) I thought it might be interesting to read an account of the rise of theory from a decidedly non-reactionary viewpoint (i.e., not Harold Bloom's). In particular, Williams' idea of formalist theory's historical delay in reception that led to its being in effect used as a weapon against a more fully developed version of itself is really provocative, ironically calling to mind some of Derrida's writing about autoimmunity and parasites. And with its 80s-eye view of the situation and typical Williams clarity and toughness, it makes a good companion piece to Rabaté's equally useful Gallic perspective in The Future of Theory. Anyway, here goes (I've highlighted some key terms and sentences to make it easier to read schematically):

Remember when Jeremy was talking in our seminar about the need at Princeton for a course that traces the history of literary theory from Russian Formalism through French structuralism/poststructuralism and American deconstruction and into its current phase of disciplinary/international diaspora? Well, I just came across such a history, in miniature, and admittedly from a partisan position, by Raymond Williams. It's taken from the appendix of The Politics of Modernism, which is the transcript of a public conversation between Williams and Edward Said in 1986. Whether you agree or not with the polemical points of Williams' narrative (and probably none of us really know enough about the subject to be sure about that yet; certainly I don't) I thought it might be interesting to read an account of the rise of theory from a decidedly non-reactionary viewpoint (i.e., not Harold Bloom's). In particular, Williams' idea of formalist theory's historical delay in reception that led to its being in effect used as a weapon against a more fully developed version of itself is really provocative, ironically calling to mind some of Derrida's writing about autoimmunity and parasites. And with its 80s-eye view of the situation and typical Williams clarity and toughness, it makes a good companion piece to Rabaté's equally useful Gallic perspective in The Future of Theory. Anyway, here goes (I've highlighted some key terms and sentences to make it easier to read schematically):"[Russian] Formalism was a reaction against what was called in the early stages a crude sociologism, which never really looked at the work at all but looked at elements which could be extracted from it and handled in other transferred ideological terms, or else simply related a text to the conditions of its production. Now the first phase of the response to that is to say that however important those questions may be, we also have to look at what the work specifically is. And this insistence has to be understood within the context of the debate. We need then to look at the second stage of the formalist argument, in the mid and late twenties, in works which have received much less publicity. Works with that tangled authorship of Bahktin, Voloshinov, Medvedev are much less well known in the West … than Shlovsky and Eikhenbaum and so on. It was agreed: let us look at what is specific in the text. But looking at what is textually specific does not rule out, rather it encourages, new ways of exploring the relations between the creation of something very specific and these more general conditions. Then, as against the previous practice which has not looked analytically at the work but which had gone straight to what was extractable as ideology or as general social conditions of authorship, let us indeed go specifically to the text as a way of finding new methods of analysing the relations between its precise composition and these conditions.

"Now this kind of work is what has been called, in Britain especially, Cultural Studies. I mean the break of Cultural Studies in the fifties from an earlier kind of sociological and indeed so-called Marxist study was precisely that it started from the close analysis of works. The contrast couldn't be more marked with earlier positions which had postulated a bourgeois economy and then a bourgeois ideology. Whereas, [Cultural Studies] starts from the texts themselves … But what it does not do, what it refuses to do, is to stop at that point. Now precisely the version of formalism that was imported and intensively propagated was to say 'and when you have done that, there is no more to do.' [Here's where I'd place the early Marjorie Perloff, circa The Poetics of Indeterminacy, whose Russian Formalist-influenced re-reading of Modernism is still so influential.] Although in fact the second stage of the formalist argument that was lost from the late twenties, and that is still not properly perceived and understood, was that when you have done that, you then have the problem of finding ways in which to analyse those specificities of the work or text, which uncover new kinds of evidence that weren't available by other methods. Then you can ask in new ways, how is the specific kind of literariness produced? How are certain forms produced? How do certain negations and absences which can be well identified by formalist methods constitute themselves in the social and historical structure? And suddenly you're into a new kind of inquiry."

OK, here's the really crucial part:

"But just at the moment that this work was making progress, back came — in a fifty-year historical delay, going via the United States and France and reappearing intensively propagated there — the old first stage of the argument, as if there had been no more move beyond it either by that Leningrad School of the late twenties, or in many of the developments in Cultural Studies in the West. The new formalism started as if it were fighting an enemy which no longer existed: the enemy which did not start analysis from specificities, but postulated the big abstractions of a society and economy and ideology, on a base-and-superstructure model, and then deduced the work, leaving many of the facts of the composition of the work unaddressed. And then we were asked to choose in this absurd way between work which was very specific within the texts and which said it didn't interest itself in other questions, and work which was still projected as talking only about reading publics, audiences, social conditions of writers or the most general facts of history. Yet in fact the other real work had been done.

"One is then very sad when the kind of propagation of theory that went on — including incidentally the reference to Saussure which was almost entirely misleading, even at times fraudulent, because it was never the representation of the whole of what Saussure had said — takes over from the development of actual new work. It's a very long and difficult job, how to carry through this powerful task, which is to see how, in the very detail of composition, a certain social structure, a certain history, discloses itself. This is not doing any kind of violence to the composition. It is precisely finding ways in which forms and functions, in very complex ways, interact and interrelate. That was what we were doing. I think the interruption is now over [wishful thinking, clearly], but I do want to say that I think it has been extraordinarily damaging, especially since theory — so-called — is much easier than this actual analytical work. You only have to read the five points of formalist technique or the three distinguishing marks of a dominant ideology; I mean you can write it in a notebook and you can go away and give a lecture on it the next day. Or write endless books about it. It's an extraordinarily easy intellectual practice. Whereas this other analytic task is difficult, because the questions are new each time. And until the last few years [?] there was this very complicated business of finding your way around what was called Theory [a still critical business, which now seems to be considered the preserve of "legitimate autodidacticism," at least at Princeton]. It failed to understand what kind of theory cultural theory is. Because cultural theory is about the way in which specific works relate to structures which are not the works. That is cultural theory and it is in better health than it is represented." (The Politics of Modernism, 183-185)

Labels:

Cultural Studies,

Perloff,

Rabaté,

Raymond Williams,

Russian Formalism,

Said,

Saussure,

Theory

Friday, September 21, 2007

Architects are Ridiculous

So I'm reading some architectural documents from 1943-1968. And they are hilarious. A: A lot of architects just simply can't write. Frank Lloyd Wright for instance. Horrible writer (My best friend's an architect. They stop writing papers sophomore year, if not earlier, so I understand how this happens)

B: They're incredibly funny. Architects have to please so many people, give speeches, schmooze bosses, clients, public, administrators, they have a real rhetorical sense. So in a post-manifesto society they take the best of the manifesto style and mix it with humor. (this isn't true of all of them, but the ones I like. Some take themselves WAY to seriously and just sound like satire)

C: Robert Moses was a real asshole. I want to reserve judgment until I read the Caro biography and some of the revisionist bios that came out earlier this year, but reading his documents...i think he sucks. He calls everyone a dirty commie. EVERY ARCHITECT.

D: This is my favorite quote for now from the brilliantly named essay "A City Is Not a Tree" by Christopher Alexander in 1965:

"The playground, asphalted and fenced in, is nothing but a pictorial acknowledgment of the fact that 'play' exists in an isolated concept in our minds. It has nothing to do with the life of play itself. Few self-respecting children will even play in a playground."

So, have more respect for yourself, kids and break out.

B: They're incredibly funny. Architects have to please so many people, give speeches, schmooze bosses, clients, public, administrators, they have a real rhetorical sense. So in a post-manifesto society they take the best of the manifesto style and mix it with humor. (this isn't true of all of them, but the ones I like. Some take themselves WAY to seriously and just sound like satire)

C: Robert Moses was a real asshole. I want to reserve judgment until I read the Caro biography and some of the revisionist bios that came out earlier this year, but reading his documents...i think he sucks. He calls everyone a dirty commie. EVERY ARCHITECT.

D: This is my favorite quote for now from the brilliantly named essay "A City Is Not a Tree" by Christopher Alexander in 1965:

"The playground, asphalted and fenced in, is nothing but a pictorial acknowledgment of the fact that 'play' exists in an isolated concept in our minds. It has nothing to do with the life of play itself. Few self-respecting children will even play in a playground."

So, have more respect for yourself, kids and break out.

Thursday, September 20, 2007

Who De Man?

(Sorry for the post title: I almost literally couldn't resist.)

(Sorry for the post title: I almost literally couldn't resist.)So……… Blindness and Insight. It's terrific! In particular, for my purposes, it's incredibly useful, since it's largely concerned (in its first two and last two chapters, anyway, which are the ones I read) with a triangulation of international critical discourses: the Anglo-American academic New Criticism (or what was left of it by the late sixties); French structuralism/poststructuralism associated with Barthes, Tel Quel, and Derrida; and, perhaps most importantly, the mainstream tradition of Continental literary history and criticism that De Man reps for (but which he sees as in danger of becoming obsolete).

PDM's initial point, in his first two essays ("Criticism and Crisis" and "Form and Intent in the American New Criticism"), is that the Anglo-American critical establishment has long ignored the work, and refused the theoretical rigor, of the Continental tradition, despite the fact that many of its leading lights ended up living and working in America (he names Erich Auerbach, Leo Spitzer, Georges Poulet and Roman Jakobson, and one could add Adorno, Renato Poggioli and, ahem, De Man himself). Instead it was content to follow out the largely untheorized, and geographically provincial, implications of the New Criticism as it descended from Eliot, Empson, and I.A. Richards (my genealogy, not De Man's) and for this reason was doomed from the start. So far, this is an old story: English and American arrogance and narrow-mindedness, refusing the fruits of the mind of Europe: close-reading as unilateralism. Yet De Man details all of the above only as a prelude to his main point, which addresses the emerging discourse of poststructuralism. As he ominously puts it, "today, it is too late to bring about this kind of encounter" (21). Because now (1967) new developments in France are calling that tradition radically into question, along with the blinkered Anglo-American one. This already complicates any narrative that would see what happens in the 70s as America (and, to a lesser extent, England) "absorbing the Continental literary critical tradition": rather, what we absorb is a response to that tradition, a revolt against it, much as centuries earlier we absorb the ideas and rhetoric of the French Revolution without the specific experience of absolute monarchy that those ideas were developed against. Which is not to say the ideas, once absorbed, are "just ideas," or have no use-value in their new context. As De Man puts it at the end of "Literary History and Literary Modernity": "the bases of historical knowledge are not empirical facts but written texts, even if these texts masquerade in the guises of wars or revolutions" (165). One tradition's revolution is another's foundation.

This is helpful. I'm not entirely convinced by De Man's philosophical attacks on the intentional fallacy in the second essay, "Form and Intent in the American New Criticism," even though I think I'm ultimately on the same side as he is w/r/t intentionality. Furthermore, De Man's rhetoric partakes of a certain "dog-pile on New Criticism" zeitgeist of the late 1960s, allowing him to completely ignore (though probably honestly: he may never have read them) an "other tradition" of American criticism which is perhaps closer to the European model, and where we could include Wilson, Burke, and Trilling. The reduction De Man seems to make — that English and American literary history and criticism is New Criticism, as theorized by Wimsatt and Beardsley — is in many ways just as disastrous as the error he warns against, that of conflating French poststructuralism with European literary criticism tout court.

Moving quickly, aren't we? I skipped Chapters III-VII, on Binswanger, Lukács, Blanchot, Poulet and Derrida, never to return (well, maybe someday). That brings us to "Literary History and Literary Modernity," which is probably De Man's most crucial intervention in the modernism/modernity debates. This one is worth dealing with on more theoretical terms, as it is an essentially an attack on the idea of modernism — that is, on the idea of modernity having useful reference to questions of literature or aesthetics. To put it succinctly, De Man's position is that all literature (all "authentic" literature, that is) is modern, or begs the question of modernity, not just so-called "modernism." This is because, whether or not the aesthetic quality that could be accurately called modernist — a quality of foregrounding the historical moment in which the work of art is produced — is present in the work, even the most minimal act of reading is a dialectic between past and present, now and then. "The ambivalence of writing is such that it can be considered both an act and an interpretative process that follows after an act with which it cannot coincide … The appeal of modernity haunts all literature" (152). Leaving aside the question of how we feel about De Man's seeming jump from structural property to theme in this passage, or whether we need a micro/macro distinction to distinguish historical time from what we might call "reading reaction time," it must be admitted that on its own terms De Man's argument is powerful: and one can easily see how it could be used as an excuse for many academics to stop thinking seriously about the problem of Modernism, and the canon of texts it had produced and continued to produce, for many years.

There's a sociological element here, of course, which De Man is admirably up front about: there is a modernism, an avant-garde, that he cares about, and it is not literary but critical. "Certain forces that could legitimately be called modern and that were at work in lyric poetry, in the novel, and the theater have also now become operative in the field of literary theory and criticism," he writes. "… This development has by itself complicated and changed the texture of our literary modernity a great deal" (143-144). I should say so! This essay itself is just such a radical complication and change. In De Man's penultimate paragraph, he takes issue with practically every form of criticism then operating in the United States. To wit: "A positivistic history that sees literature only as what it is not (as an objective fact, an empirical psyche, or a communication that transcends the literary text as text) is … necessarily inadequate." That takes care of Marxism, psychoanalysis, cultural studies, and traditional progressivist literary history. "The same is true of approaches that take for granted the specificity of literature (what the French structuralists, echoing the Russian formalists, call literarity [littérarité] of literature)," and here lie Northrop Frye and the remnants of the American New Criticism as well. (Note that all of the above movements were articulated in response to the emergence of Modernism and the avant-garde, and that most of them, in their late 60s form at least, tended to privilege that tradition.) "If literature rested at ease within its own self-definition," De Man says, "it could be studied according to methods that are scientific rather than historical," although he implies that such a state of rest is in fact illusory and impossible. "We are obliged to confine ourselves to history when this is no longer the case, when the entity steadily puts its own ontological status into question" — as in the period of Modernism, when the first set of critical methods that De Man now deems "inadequate" were developed. What replaces these failed experiments, which are unable in themselves to come to terms with literature qua literature? Glad you asked: it is, of course, deconstruction (not yet named as such), which as a practice is loftily unconcerned with the petty historical and formal questions that constitute all previous discussions of "modernism" in literature; thus, "the critical method which denies literary modernity would appear — and even, in certain respects, would be — the most modern of critical movements" (164).

This is a clarion call for the big flip-flop of the 1970s: the decade in which academic literary criticism stops lagging behind the avant-garde trying to unravel its mysteries and starts being the avant-garde, in the literal sense of the words, setting the agenda for poets, artists, and (to a lesser extent) novelists and adopting an oppositional and adversarial attitude to the culture at large. It's the necessary fact to explain the rise of the L=A=N=G=U=A=G=E poets as well as, in many ways, our poetic and academic cultures in America today. It's also where I get off, for the time being — hey, look at the time! It's 1970.

Labels:

1970s,

Criticism,

De Man,

Deconstruction,

L=A=N=G=U=A=G=E,

New Criticism,

Theory

Lesson for a Boy

Want an alternative to the Attridgean metrical system we learned that actually tallies with what other critics and poetry readers understand by English prosody? I thought so. Here's a little mnemonic ditty by Samuel Taylor Coleridge, written in 1803 for his son Derwent (does that remind anyone else of a De La Soul album?). Warning: it gets a little mushy at the end.

Want an alternative to the Attridgean metrical system we learned that actually tallies with what other critics and poetry readers understand by English prosody? I thought so. Here's a little mnemonic ditty by Samuel Taylor Coleridge, written in 1803 for his son Derwent (does that remind anyone else of a De La Soul album?). Warning: it gets a little mushy at the end.LESSON FOR A BOY

Trochee trips from long to short;

From long to long in solemn sort

Slow Spondee stalks; strong foot! yea ill able

Ever to come up with Dactyl trisyllable.

Iambics march from short to long; --

With a leap and a bound the swift Anapests throng;

One syllable long, with one short at each side; --

First and last being long, middle short, Amphimacer

Strikes his thundering hoofs like a proud highbred Racer.

If Derwent be innocent, steady, and wise,

And delight in the things of earth, water, and skies;

Tender warmth at his heart, with these metres to show it,

With sound sense in his brains, may make Derwent a poet, --

May crown him with fame, and must win him the love

Of his father on earth and his Father above.

My dear, dear child!

Could you stand upon Skiddaw, you would not from its whole ridge

See a man who so loves you as your fond S.T. COLERIDGE.

Monday, September 17, 2007

Moore, Moore, Moore

Sunday, September 16, 2007

Remembering the Thirties

By Donald Davie:

By Donald Davie:I

Hearing one saga, we enact the next.

We please our elders when we sit enthralled;

But then they're puzzled; and at least they've vexed

To have their youth so avidly recalled.

It dawns upon the veterans after all

That what for them were agonies, for us

Are high-brow thrillers, though historical;

And all their feats quite strictly fabulous.

This novel written fifteen years ago,

Set in my boyhood and my boyhood home,

These poems about "abandoned workings," show

Worlds more remote than Ithaca or Rome.

The Anschluss, Guernica — all the names

At which those poets thrilled or were afraid

For me mean schools and schoolmasters and games;

And in the process some-one is betrayed.

Ourselves perhaps. The Devil for a joke

Might carve his own initials on our desk,

And yet we'd miss the point because he spoke

An idiom too dated, Audenesque.

Ralegh's Guiana also killed his son.

A pretty pickle if we came to see

The tallest story really packed a gun,

The Telemachiad an Odyssey.

II

Even to them the tales were not so true

As not to be ridiculous as well;

The ironmaster met his Waterloo,

But Rider Haggard rode along the fell.

"Leave for Cape Wrath tonight!" They lounged away

On Fleming's trek or Isherwood's ascent.

England expected every man that day

To show his motives were ambivalent.

They played the fool, not to appear as fools

In time's long glass. A deprecating air

Disarmed, they thought, the jeers of later schools;

Yet irony itself is doctrinaire,

And curiously, nothing now betrays

Their type to time's derision like this coy

Insistence on the quizzical, their craze

For showing Hector was a mother's boy.

A neutral tone is nowadays preferred.

And yet it may be better, if we must,

To praise a stance impressive and absurd

Than not to see the hero for the dust.

For courage is the vegetable king,

The sprig of all ontologies, the weed

That beards the slag-heap with his hectoring,

Whose green adventure is to run to seed.

(1953)

Saturday, September 15, 2007

Best.Novel.Ever.

"With every deep breath Herf breathed in rumble and grind and painted phrases until he began to swell, felt himself stumbling big and vague, staggering like a pillar of smoke above the April streets, looking into the windows of machineshops, buttonfactories, tenementhouses, felt of the grime of bedlinen and the smooth whir of lathes, wrote cusswords on typewriters between the stenographer's fingers, mixed up the pricetags in departmentstores. Inside he fizzled like sodawater into sweet April syrups, strawberry, sarsaparilla, chocolate, cherry, vanilla dripping foam through the mild gasolineblue air. He dropped sickeningly fourtyfour stories, crashed. And suppose I bought a gun and killed Ellie, would I meet the demands of April sitting in the deathhouse writing a poem about my mother to be published in the Evening Graphic?

He shrank until he was of the smallness of dust, picking his way over crags and bowlders in the roaring gutter, climbing straws, skirting motoroil lakes."

So Manhattan Transfer is officially the best novel in the world. I was telling Greg yesterday that it's better than Gatsby, better than Hemmingway's best (well...maybe not the short stories...but definitely better than Sun). Might even give Faulkner a run for his money.

It came out in 1925 and certainly defines that era better than Gatsby or Hemmingway. It is the first novel I've read that is able to create the modern city while getting out from under the thumb of Ulysses. While some of the techniques are the same (the use of headlines, jumping between consciousness of characters), it comes off as being such a different novel. For one thing, it's more filmic than Joyce's writing. Apparently, Eisenstein was one of Dos Passos' influences, but what he does is not quite montage in the Eisensteinian sense. At the beginning of each chapter, he does have an extraneous paragraph describing a scene of city life, but it's not quite unconnected enough to be true montage. This is the beauty of the writing--it all works together in brushstrokes, almost to make this larger unseemly whole. Kinda like a Chuck Close painting. But it also manages to move forward, with a thumping plot-rises constantly.

The novel exists in constant motion that is never not exhilirating. There are about 150 characters, probably. But it works. It jumps from the announcement of New York as the "World's second metropolis" in the papers to a post WWI New York seamlessly. Dos Passos is responding to Dreiser and the realists/naturalists AND the avant-gardists and making this new breathing thing. And it's a pretty seedy novel as well. I haven't read an American novel that deals with prostitution or abortion so bluntly from this early in the 20th century.

The compound words work to visually create the motion and the grafting that the city he is describing is composed of. You know how people say that the city of a novel becomes a character? (which is so cliche, I HATE that saying...of course it's a character.) Anyway, Dos Passos is reimagining the idea of character in this novel. There are too many people in the novel for them to be characters, so how does one describe the actors in the book? Words and accents and style and jump cuts all get in the way, leaving character a very ambiguous idea.

Another interesting bit is that Dos Passos is SO ambitious in this novel...narrating every type of voice, from destitute immigrants to capitalists to architects and dancehall ladies to bootleggers. BUT, he stays clear away from Harlem and there are no black characters. There are Jewish, Italian, English, French characters with matching dialect. But there is no black dialect at all. Black characters exist amongst the melay, and get descriptions like this: "The elevatorman's face is round ebony with ivory inlay"--and that's the extent of it. The closest the novel gets to a black character is Congo Jake who looks black, but is really Italian. So for all this motion and movement, no Harlem nor Renaissance. Which is FASCINATING because Home to Harlem was such a big seller only a few years earlier as well as Van Vechten's novel. So Dos Passos had to be aware and had to have made a conscious decision to extract a certain type of black urbanity from the novel. A response to Pound and Eliot with this omission? A nod to James Weldon Johnson? i dunno.

Anyways, point being, if I teach 20th century American fiction, this book will definitely be on that list.

He shrank until he was of the smallness of dust, picking his way over crags and bowlders in the roaring gutter, climbing straws, skirting motoroil lakes."

So Manhattan Transfer is officially the best novel in the world. I was telling Greg yesterday that it's better than Gatsby, better than Hemmingway's best (well...maybe not the short stories...but definitely better than Sun). Might even give Faulkner a run for his money.

It came out in 1925 and certainly defines that era better than Gatsby or Hemmingway. It is the first novel I've read that is able to create the modern city while getting out from under the thumb of Ulysses. While some of the techniques are the same (the use of headlines, jumping between consciousness of characters), it comes off as being such a different novel. For one thing, it's more filmic than Joyce's writing. Apparently, Eisenstein was one of Dos Passos' influences, but what he does is not quite montage in the Eisensteinian sense. At the beginning of each chapter, he does have an extraneous paragraph describing a scene of city life, but it's not quite unconnected enough to be true montage. This is the beauty of the writing--it all works together in brushstrokes, almost to make this larger unseemly whole. Kinda like a Chuck Close painting. But it also manages to move forward, with a thumping plot-rises constantly.

The novel exists in constant motion that is never not exhilirating. There are about 150 characters, probably. But it works. It jumps from the announcement of New York as the "World's second metropolis" in the papers to a post WWI New York seamlessly. Dos Passos is responding to Dreiser and the realists/naturalists AND the avant-gardists and making this new breathing thing. And it's a pretty seedy novel as well. I haven't read an American novel that deals with prostitution or abortion so bluntly from this early in the 20th century.

The compound words work to visually create the motion and the grafting that the city he is describing is composed of. You know how people say that the city of a novel becomes a character? (which is so cliche, I HATE that saying...of course it's a character.) Anyway, Dos Passos is reimagining the idea of character in this novel. There are too many people in the novel for them to be characters, so how does one describe the actors in the book? Words and accents and style and jump cuts all get in the way, leaving character a very ambiguous idea.

Another interesting bit is that Dos Passos is SO ambitious in this novel...narrating every type of voice, from destitute immigrants to capitalists to architects and dancehall ladies to bootleggers. BUT, he stays clear away from Harlem and there are no black characters. There are Jewish, Italian, English, French characters with matching dialect. But there is no black dialect at all. Black characters exist amongst the melay, and get descriptions like this: "The elevatorman's face is round ebony with ivory inlay"--and that's the extent of it. The closest the novel gets to a black character is Congo Jake who looks black, but is really Italian. So for all this motion and movement, no Harlem nor Renaissance. Which is FASCINATING because Home to Harlem was such a big seller only a few years earlier as well as Van Vechten's novel. So Dos Passos had to be aware and had to have made a conscious decision to extract a certain type of black urbanity from the novel. A response to Pound and Eliot with this omission? A nod to James Weldon Johnson? i dunno.

Anyways, point being, if I teach 20th century American fiction, this book will definitely be on that list.

Friday, September 14, 2007

Takes one to know one

Philip Larkin on Thomas Hardy and the codger question:

Philip Larkin on Thomas Hardy and the codger question:"Without doubt Hardy, like others of his century, was forever on the look-out for some sign that humanity was improving, and his failure to perceive one produced many occasional bitter utterances ('After two thousand years of mass / We've got as far as poison gas'), and it is curious to note that both he and Shaw see time as a necessary ingredient of man's spiritual and moral advance. Shaw's view is that we must live longer: Hardy's is rather that we must get old quicker or, like the little boy 'Father Time,' be born old. Both, in their different ways, are asking man to grow up." (Required Writing, 171-172)

Thursday, September 13, 2007

C'mere, you

I have a tremendous critical crush on Lionel Trilling. It's the dangerous kind of crush, one where you're not quite sure you really ought to like the other person, or whether your friends would approve: a certain sense of "What am I getting myself into here?" attends my reading, especially of his more sweeping and impressive moments. After all, Trilling in many ways represents what the radical energies of the 60s and 70s swept away, not without some very good reasons; and his general theoretical bent, though emerging out of Trotskyism and addressing itself to fellow liberal intellectuals of the 1940s, is usually seen as a harbinger of neoconservatism (the most substantial recent article I could find on him is from the Weekly Standard, which gives you some idea).