Rematch! This time Eliot fared a litle better: I read his two works published in 1925, "The Hollow Men" and two scenes from his unfinished first play Sweeney Agonistes. What I'll remark on here is the fact that, three years after The Waste Land, it's as if Eliot has wholly compartmentalized the two sides of his poetic personality: "The Hollow Men" has all the oracular gravitas, the violent imagery, the mantraic repetitions, the dried-out landscape, just as if it were a continuation of "What the Thunder Said." Sweeney Agonistes, on the other hand, has all the dark humor, dramatic interest, and fascination with pop culture and the underclasses typical of "The Burial of the Dead," "A Game of Chess" and "The Fire Sermon." I wonder if this was a reaction to negative criticism of The Waste Land as being too divided, or schizophrenic? It would be interesting to compare Eliot's use of repetition in the two works: the first operating more, I guess, "poetically" (the words taking on strength and symbolic/rhetorical power through reiteration), and the second more idiomatically, to indicate the inadequacy of contemporary conversation. (Words to live by: "I gotta use words when I talk to you / But if you understand or if you dont / That's nothing to me and nothing to you / We all gotta do what we gotta do," Complete Poems, 84). Of course, the two might not really be so different after all… In any case, I find Sweeney (which I'd never read before) by the far the more intriguing piece of writing, particularly in its recordings of the language of American businessmen (named, um, Klipstein and Krumpacker), an idiom which Eliot had now been separated from for about a decade. (There are no Americans in The Waste Land, are there?) There's a kind of conflicted loving irony in the way Eliot presents these characters; it reminds me of John Ashbery's remarks about his addiction to American newspapers and comic books when he was living in Paris in the early 60s.

Rematch! This time Eliot fared a litle better: I read his two works published in 1925, "The Hollow Men" and two scenes from his unfinished first play Sweeney Agonistes. What I'll remark on here is the fact that, three years after The Waste Land, it's as if Eliot has wholly compartmentalized the two sides of his poetic personality: "The Hollow Men" has all the oracular gravitas, the violent imagery, the mantraic repetitions, the dried-out landscape, just as if it were a continuation of "What the Thunder Said." Sweeney Agonistes, on the other hand, has all the dark humor, dramatic interest, and fascination with pop culture and the underclasses typical of "The Burial of the Dead," "A Game of Chess" and "The Fire Sermon." I wonder if this was a reaction to negative criticism of The Waste Land as being too divided, or schizophrenic? It would be interesting to compare Eliot's use of repetition in the two works: the first operating more, I guess, "poetically" (the words taking on strength and symbolic/rhetorical power through reiteration), and the second more idiomatically, to indicate the inadequacy of contemporary conversation. (Words to live by: "I gotta use words when I talk to you / But if you understand or if you dont / That's nothing to me and nothing to you / We all gotta do what we gotta do," Complete Poems, 84). Of course, the two might not really be so different after all… In any case, I find Sweeney (which I'd never read before) by the far the more intriguing piece of writing, particularly in its recordings of the language of American businessmen (named, um, Klipstein and Krumpacker), an idiom which Eliot had now been separated from for about a decade. (There are no Americans in The Waste Land, are there?) There's a kind of conflicted loving irony in the way Eliot presents these characters; it reminds me of John Ashbery's remarks about his addiction to American newspapers and comic books when he was living in Paris in the early 60s.As for Pound, I read the first sixteen Cantos (first published together in 1925). If Eliot was trying to separate out the strands of his sensibility in this period, Pound was clearly going in the other direction: developing the "ply over ply," hopelessly texturally enmeshed style that becomes literally inescapable for him in his later work. I don't have much to say about The Cantos (yet) except that they become much more fun to read over time, once you stop worrying about "getting it" (or worse, agreeing with it) safe in the knowledge that no-one ever really has or will and just bask in its shameless Poundness. I also never noticed before how many animals there are in the beginning of the poem, especially cats. Modernists love their critters!

Winner: Eliot.

Tuesday: Langston Hughes vs. E.E. Cummings

What these two dudes have in common is a reliance on a semi-consistent "poet" persona: they both usually write in the first person, tackle time-honored topics like love, nature and sadness, and in many ways dispense with more than a century's worth of abstruse poetic theory in order to embody the good old Wordsworthian values of "a man speaking to men" and "emotion recollected in tranquility." Though adopting such a mode might seem like the path of least resistance today, in the context of both High Modernism and traditional verse culture of the 1920s, it does feel fairly radical — and, of course, radically populist.

What these two dudes have in common is a reliance on a semi-consistent "poet" persona: they both usually write in the first person, tackle time-honored topics like love, nature and sadness, and in many ways dispense with more than a century's worth of abstruse poetic theory in order to embody the good old Wordsworthian values of "a man speaking to men" and "emotion recollected in tranquility." Though adopting such a mode might seem like the path of least resistance today, in the context of both High Modernism and traditional verse culture of the 1920s, it does feel fairly radical — and, of course, radically populist.I think Hughes could do this because he was stepping into a cultural role that, by 1926 when The Weary Blues was published, was firmly, if newly, defined: that of a "Negro poet." Because writers like Countee Cullen and Claude McKay had preferred to demonstrate competence in traditional English versifying in order to back up their claims of racial and social equality, Hughes' insistence on using loose, non-English forms like the blues and Whitmanian free verse is especially provocative, opening himself up to hostile charges of simplicity, primitivism, or illiteracy. But it also gives his work the force of naturalness, and allows his inexhaustible talent for image selection and turn of phrase maximum room to maneuver. (I'm also interested, and this something to return to, in the traces here and there of a Symbolist inheritance in Hughes, though, particularly from Verlaine, in a poem like "Black Pierrot," for instance. What did Hughes read?)

One could make the argument that Cummings is playing with the expectations engendered by a similar readymade role, "the modern (or modernist) poet." Cummings' first book was published in 1922, the year of The Waste Land and Ulysses, "the year modernism broke," making him sort of New Wave to Joyce and Eliot's Punk: the slightly belated successor who can come in and benefit from the cultural capital accrued by previous experimentation (it is true, I think, that Cummings was more popular, at least in America, than any of the more reputable High Modernists). Cummings, at least by the time of is 5 (which I read), is aware of this precarious position and uses it to generate effects within his poetry: "what's become of (if you please) / all the grandja / that was dada?" (is 5, 11). Likewise all his unabashed liking for jazz and Krazy Kat, which Greg's analyzed well already. In Cummings, I see one of the first American expressions of what Stanley Cavell eventually comes to call a signal feature of modernist art: "the possibility of fraudulence" (Must We Mean What We Say?, 176). He exaggerates the distance between his technical oddity and his lyrical ego to the point where he's almost a "poet" before he is a writer of poetry. (One indicator of Cummings' almost Duchampian provocativeness is his extensive treatment in Laura Riding and Robert Graves' 1927 Survey of Modernist Poetry, which effectively calls Cummings' bluff by deciding that he is a real poet after all — just not a very interesting one.)

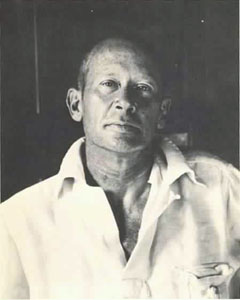

In any case, I think he certainly sets the stage for the Beats, and their particularly male forms of poetic self-display (and incidentally, take a look at that photo: EEC's definitely the buffest Modernist by a considerable margin).

Winner: Hughes. When it comes down to it, Cummings, for all his historical importance and surface amiability, is just too jokey — without being all that funny.

I'm going to stop at hump day for the time being, but there's more to come. Next up: Hart Crane vs. the Atlantic Ocean!